|

Well, my adventure in Mongolia is now history.

There were many surprises on the trip, the first being the route our aircraft took. I expected to leave Los Angeles International Airport and immediately be over the ocean (given that it's runway ends about 2,000 feet from the shore). I had a window seat on the right side of the plane, and for the first half of the trip we stayed either in sight of land, or over it. Our route took us up the West Coast of the United States. I saw the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, followed by the cities of Portland, Seattle, and Anchorage. This route is called a "Great Circle". On flat maps of the world, the route doesn't make sense, but laid over a globe, one can see that it is, in fact, significantly shorter. This image (lifted off the web) only approximates our route. After leaving Alaska, we passed over the Bearing Straights, parts of Russia (Siberia), and finally descended into Beijing, China. From there we took a connecting flight to the famous Ghinggis Khaan International Airport in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. |

The aircraft was a Boeing 777, that came equipped with a video monitor in the back of each seat, such that every passenger had his or her private screen. You could watch movies, play video games, read books (very limited choices if you don't read Chinese), listen to music, or (my favorite) have a display that tracked the progress of the aircraft along its route. You could choose to see the view out of the left or right sides of the plane, or the cockpit. Also included was a readout of the ground speed, altitude, outside air temperature, time since departure, and estimated time of arrival. I'm sorry my camera didn't focus adequately to do it justice, but I loved that feature. Sitting in the same narrow seat for 12.5 hours was very difficult, but without the information provided by this display, it would have been almost impossible. For those of you who are tired of answering the question, "Are we almost there yet?" perhaps you should consider a similar display for the pint-sized passengers stuck in the rear seat of your vehicles...

|

|

In the early 1200's Ghinggis Khaan united the scattered and factious Mongol tribes, assembled his famous (or infamous) Mongol Hordes, and began a conquest that eventually resulted in the capture of most of Asia and Europe. This warrior's given name was Temujin. "Ghinggis Khaan" is actually a title, with Ghinggis meaning, "from sea to sea", and Khaan meaning, "supreme ruler". Given the paucity of resources evident in Mongolia now, it is difficult to understand how he accomplished that task. He is revered by the Mongolian people, and almost everyone claims to be a descendent of his. Records kept by nations he vanquished are not as flattering, and suggest that sometimes his armies, at his command, systematically slaughtered millions of captured civilians. This statue of him was completed in 2010, and stands 131 feet tall. It is a marvel of engineering. We climbed up to an observation deck on the back of the horse's neck, and found no give or sway to the structure; it is absolutely stable. The building below houses a very impressive museum (but you had to pay extra to take pictures inside). A quote attributed to Temujin suggests that the reason he wanted to conquer the world was to end warfare and establish peace. At first blush that sounds a little contradictory, but consider for a moment that WWI was often billed as, "The war to end all wars", and maybe it doesn't sound as foreign as it might...

|

|

Mongolia is a mixture of the ultra modern and the archaic. Cell phones are common but indoor plumbing is not. This is one of two stalls in the outhouse for our apartment in Ulaanbaater and is typical of those in the city. When ambient temperature is below zero, (a common occurrence in the winter) I imagine one would not spend unnecessary time here. Further, (given the gaps in the rough lumber walls) a neighbor who had a wandering eye could become much better acquainted with you than you might like...

|

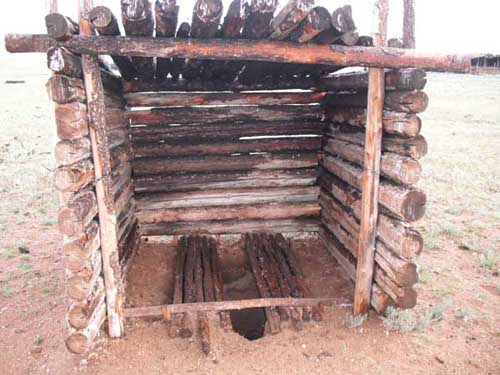

This is the country version of the same thing. The pit here is only about 1 meter deep, opposed to the 5 meters of the city version. Further, note the complete absence of a door...

|

|

|

This one was part of a clean new service station along one of the rare paved roads. It doesn't make sense to spend this much space on outhouses, but I had trouble believing my own eyes, and chose to document what I saw. I admit to being pampered and spoiled, but I really like indoor plumbing. We had to boil our drinking water and, as you might imagine, that was a bit inconvenient. I have no idea how Mongolians wash their clothing, but clean, bright white blouses and t-shirts are common. To shower, we had to travel to a facility about 5 blocks away and (when we could find them open) rent a stall for a nominal amount. I have a low flow shower head in my bathroom, but would have to plug about 80% of it's orifices and reduce it's pressure by about 90% to approximate the ones in Mongolia. Even so, the occasional shower was, perhaps because of the surrounding circumstances, even more enjoyable than the ones I take here every morning.

|

While in Mongolia I experienced what it is like to be illiterate. Mongolians have an ancient alphabet that is written from top to bottom, but it is now rarely used (except as decoration). Instead, they have borrowed the Cyrillic alphabet from the Russians. When you don't recognize the letters, it is not only impossible to read the words, it is difficult to even recreate what you saw. If I were to spend any significant time in Mongolia, one of the first orders of business would be to acquire at least rudimentary reading skills.

|

|

|

Dave tells stories of people who left his previous expeditions early because they thought they were starving. I didn't find the quantity of food to be lacking, but the variety wasn't overwhelming. For breakfast we had oatmeal, and for supper we ate a stew with potatoes, carrots, and onions in varied soup base mixes. I liked the soups, but the last time I ate oatmeal (before this trip) was in Brazil and I left there in 1971. If my computational skills are still intact, that was about 41 years ago. At this point, there is a substantial probability that another 41 years will pass before I eat oatmeal again.

|

Nevertheless, I am an omnivore, and that means I can eat every kind of food. On this trip I chose to do so, even when it meant eating chunks of fat or internal animal parts that most Westerners avoid. Almost every time we encountered a town we ate in the local restaurant, even though their menu often included less than four choices. When I was confronted by a bit of something in my buuz (meat filled steamed dumpling [pronounced booze]) or khuushuur (deep fried, meat filled, pocket bread [pronounced horshsure]) or mutton stew that I could not identify, I simply turned my mind off and ate it. With the exception of an occasional chunk of gristle, it usually tasted pretty good...

|

|

|

We were in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar about a week on each end of the trip. The first week was spent acquiring and equipping a vehicle. The last week resulted from early termination of the expedition due to fatigue, illness, and vehicle uncertainties. Our attempt to fly home early was deterred by a $1000 airline ticket modification charge. UB (as it is called by its natives) is a city of about 1.3 million people, and driving there is about like driving in a large city in any other developing nation (except that cars can have their steering wheel on either the right or left hand side). Traffic lights and lines painted on the pavement mean nothing, oncoming traffic is ignored, gridlock is the norm, and horns are used more frequently than brakes. For the most part, Mongolian drivers are ferociously aggressive, but at the same time (in an odd and unexpected way), forgiving. Occasionally a honking fest will break out and last for 30 seconds or more, but nobody seems to get really upset or hold a grudge. If that much honking occurred here in the States, the result would undoubtedly be multiple homicides. While we were there, United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton came to Ulaanbaatar on an official visit. The Mongolian Police stopped traffic and completely cleared Ghinggis Avenue, one of the major routes through town. Cars and busses sat waiting on side streets for at least 45 minutes but nobody seemed to be angry about the delay, except us. We got off our bus and walked in the rain.

|

In the countryside, driving is a completely different matter, and in order to understand it, you have to totally revise the mental picture that appears when you hear the word, "road". Most of Mongolia is steppe, a smooth grassland, with almost no brush, trees, or rocks on its surface.

|

|

|

Vehicles can be driven anywhere, and motorcycles are used extensively to herd livestock. Private land ownership is beginning to take root, but in the countryside it is still rare. There are no fences and herds of livestock roam, their travel impeded only by the inclination of their herdsmen.

|

Other than the approximately 1500 miles of pavement, no road improvement has occurred. That means no graded or graveled dirt roads exist. Roads here consist of parallel tracks of denuded earth, and are created when vehicles follow the same route several times. Wet conditions caused dips and holes develop, and the road becomes rough. When this roughness becomes intolerable, traffic simply moves over 10 feet, and a new road is created. There are places where these roads have grown into a hundred sets of parallel tracks.

|

|

|

The advantage for someone studying birds of prey, is that if you see some feature on the landscape that may be of interest, you can simply point your vehicle at it and drive there.

|

Cross-country driving is, of course, not without hazard. There are places where erosion has created vertical banks, and we found a couple of these, the hard way. But as is well known, if you have a shovel and enough time, you are never really stuck. Still, it was a bit disconcerting to hear Dave say (perhaps not totally in jest), "Well, that's a surprise; we're all still alive".

|

|

|

Mongolia, like most countries in Europe, Asia, and South America, uses electric power at 220 volts. We, in the US, use 110 volts.

|

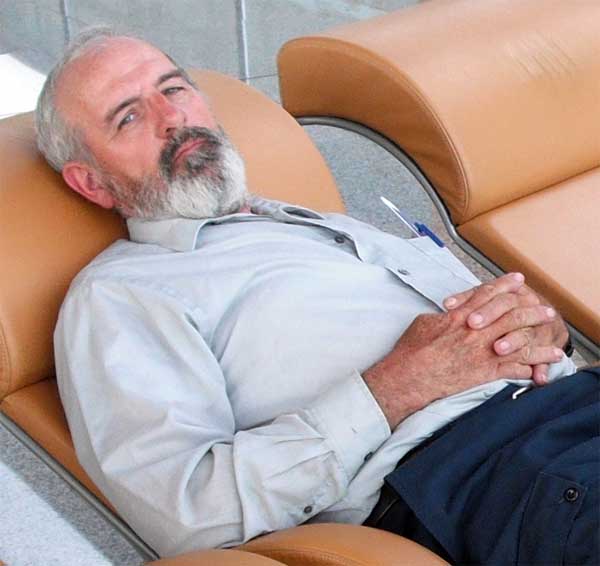

As a result, my razor didn't work and in the time I was there I went from this...

|

|

|

to this...

Much to my chagrin, I am continually growing a beard. From time to time Barbara suggests I stop shaving it. That is enticing because I don't like to shave but, unfortunately, the only thing worse than shaving, is having hair on my face. |

The point of this trip was to gather data on the food habits of golden eagles in Mongolia. The assumption is, that if the remains of an animal are found in an eagle's nest, the eagle fed that animal to it's young. Physical measurements of the nest are also recorded, along with a description of the environs, the number and age of the young, etc.

|

|

|

This necessitated visiting nest sites, and digging through the debris there. Unfortunately, eagles prefer to build their nests on real estate that is relatively vertical. This offers their young some protection against predators while the adults are away from the nest foraging. It also makes for adrenaline surges if you are not totally comfortable with "free climbing" rock faces. There were a couple of times when we chose to use the climbing gear we took with us.

|

It seemed to me that the trip was continually interrupted by car problems. Much to my surprise, we were able to solve them all, some by the application of judicious and careful reasoning, and others by the application of copious quantities of cash.

|

|

|

This being my first expedition of this kind, I didn't really know what to expect. Dave seemed satisfied with the number of new nests we located. I'm not sure exactly what the number was but I think it may lie between 15 and 20. Whatever it was, I have a mind set that is always asking, "How can we get just one more?"

|

|

A second goal of this trip was to follow up on an ongoing study of Saker Falcons, one of the largest of this type of bird in Asia. Where their ranges overlap, Saker Falcons are thought to interbreed with the Gyrfalcons. Some of the falcon nest sites were quite accessible, but I will readily admit I didn't visit any nests like this one...

|

|

|

Mongolians have a different worldview than I. When we had car problems in a village, people would always gather around and, without being invited, begin tinkering with the vehicle. It always seemed to turn out well, but I wouldn't try that in the States...

|

|

There have been rare observations of the young of upland buzzard (a large hawk) being raised by an eagle. A possible explanation is that a young buzzard was seized as a prey item, survived the trip to the eagles nest, and was subsequently misidentified by the adult eagle as it own offspring. Dave wanted a posed photo of upland buzzard young together with eagle young in the same nest, which prompted our visit to this nest. Both the young buzzards flew when we got too close, but given that they had not yet mastered that art, they were relatively easy to capture and repatriate.

|

|

|

Did I mention that our jeep had mechanical problems? |

| I suspect you might be tiring of photos depicting people rummaging through eagles' nests, but that was the point of the trip. I promise this is the last one... |

|

|

I was really taken by the ancient design of these brooms, executed in florescent neon colors. I considered flying one home to Barbara, but was afraid she might get the wrong idea... |

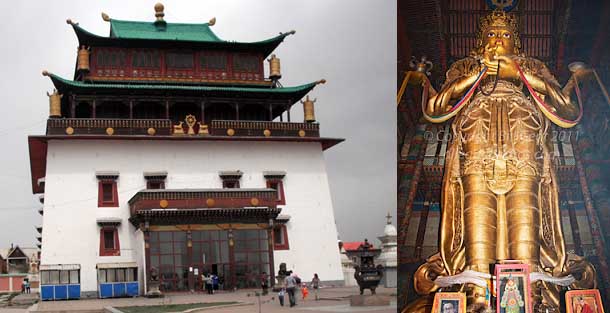

| Many Mongolians are adherents of Buddhism, and monasteries abound in the country. This one in UB houses a statue of Buddha measuring 26.5 meters tall. Visiting the temple was encouraged (for a small fee) but photography was prohibited inside, so I lifted this insert off the web. This statue, recently completed to replace the one destroyed by the communist government in 1921, is made of copper and overlaid with gold. |

|

|

Apparently cement tolerates cold burial better than wood. Every power pole I saw in Mongolia had been constructed using this same methodology. |

| Up close, the methodology appeared even stranger, but apparently it is functional. How would you like a job twisting those wires tight? It has the look of being a manual process. |

|

|

I am not one of those bird watcher who tracks and tallies the different types of birds I've as seen. But, if I were, I would have scored well on this trip. I saw numerous lammergeiers (also called bearded vultures or bone crackers), an old world bird whose diet consists almost entirely of bone. The bird often carries large bones high into the air, then drops them onto rocks to break them. I was able to witnesse this behavior on a couple of occasions. A lammergeier (feather on the right) is significantly larger than a golden eagle (feather on the left).

I also saw many kites, a bird somewhat smaller than an eagle that is a very agile flyer. In fact we observed one kite steal a small prey item from a steppe eagle. In one of the places we camped, our translator entertained us by throwing scraps of meat in the air for the kites to dive on and catch. Being able to interact with a wild bird like that seemed quite remarkable. |

|

As I mentioned earlier, Mongolia is a mixture of archaic and modern. Movable, round, one room, structures (called yerts by foreigners and gers by locals) dot the countryside. These have been around since the 13th century, and probably longer. What is new is the solar cell array, the dish-type TV antenna, and the motorcycles parked outside. In the summer when it is light from 5 a.m. until 9 p.m., the solar cells work well. In the short days of winter...well, not so much.

|

|

|

Here again is a mixture of ancient and modern. The design of these wheels (abandoned when a family moved their ger) dates back over 2000 years. The rubber tread, cut from a motorcycle tire, is a much newer concept.

|

|

On one of Daves' previous expeditions, a sheep shed like this provided refuge for his party when they were caught in a late season snowstorm. Straw stacked on top of the roof kept the interior dry. We tried this shed as protection from rain, with a little less luck. Some time after midnight, a heavy thundershower turned the roof into a sieve. I had a tarp to spread over the top of my sleeping bag, but cramps in my legs when I tried to employ it kept me from effectively covering my feet. I couldn't stand up, because I didn't want to press my sleeping bag into the 10 inches of now wet manure that comprised the floor. The result was that I lay there until morning, feeling the water slowly seep through my clothing from my feet upward. Dave (a man who has spent a night sleeping in a tree in the rain as a protection from the bears on Kodiak Island) shared this experience and characterized it as, "One of the ten worst nights of my life".

|

|

|

Climbing to nest sites, I encountered many breath-taking views. Then again, maybe it was the climb that left me gasping for breath...

|

|

Much livestock is raised in Mongolia. Sheep and goats are ubiquitous. In addition, cows, yaks (seen in the foreground of this image), and horses are all raised for food. (Yes Ameilia, the Mongolians really do eat horses [taste just like chicken].)

|

|

|

Here is more breath-taking scenery. Can you hear me panting?

|

|

Sites such as this are relatively common in the countryside. They are either burial sites or monuments. Various internet sites called them Khirigsuurs. Our translator, a native Mongolian, called them Koorgons, and said the term meant, "ancient ones". I had trouble understanding even single Mongolian words. We would arrive at a town and I would inquire as to its name. Our translator would clear his throat and cough, and that would be the name. I would do the same and make the same sounds, and he would laugh at me. Given that scenario, it is possible that the two names above are, in fact, the same. Our translator works as a tour guide and, perhaps because of that, felt that he should have the answer to all our questions. Sometimes he would pontificate at length about some subject, when I was pretty sure the correct answer was, "I don't know".

|

|

These are Eurasian Black Vultures and we saw many of them in the skies of Mongolia. They are one of the largest birds of prey in the world, with a wingspan of 8½ to 10 feet, and are only distantly related to new world vultures. These captive individuals were at a roadside stand where, for a small fee, you could have your photo taken with one standing on your fist and dwarfing you with its outstretched wings. These birds actually seemed to be enjoying themselves (or at least the food rewards that accompanied each photo session).

|

|

While driving one morning we topped a rise and visible in the distance was a cemetery. A little ways apart from the markers was a group of black dots. For some reason, I immediately knew what I was looking at. A group of perhaps a dozen black vultures were devouring a human corpse. That whole scenario was a little eerie, but the part that really got to me was the unbridled enthusiasm the birds displayed for their task. One of them jerked its head up and back while a human foot sticking out of the mass of feathers flopped from one side to the other. That is the sort of thing you never forget...

This practice is called, "sky burial", and used to be common in Mongolia. It was not allowed during the communist rule, but is said to be making a come back. After relatively elaborate ceremonies, the body is laid out on top of the ground to be eaten by scavengers. The presiding religious officials check back in a few days, and the presence of parts left un-devoured suggests that the person has not yet made it into heaven, necessitating further prayers and ceremonies. It's definitely not for me, but I suppose a rabid environmentalist might think it the perfect exit strategy. |

|

A few days later, we drove through a second cemetery where this tradition had apparently been practiced for some time. There were at least 29 skulls (that from a distance resembled white bowling balls) littering the ground.

|

|

|

Also present was this fellow (sorry about my lack of focus). The straight cuts to the skull suggest an autopsy, and if that were the case, embalming chemicals may have rendered the rest of the body unpalatable to scavengers. You have to admit it would be difficult to fabricate stories like this, but for those of you who are still skeptical, I invite you to see it for yourself at:

North 47° 48.036' East 101° 25.602' When dealing with weird, it's a good idea not to become too involved so we drove on without touching a thing... |

On this trip I found I could walk much faster if I used one of my hiking sticks, particularly when longer distances were involved. This had unintended consequences, in that almost every time I got on a bus someone (usually a young girl or a middle aged woman) would get up and offer me their seat. I was at first surprised, then appalled, and then humiliated at being perceived as decrepit old man. I'm simply not ready to play that role! I solved the problem by collapsing my stick and stowing it in my backpack prior to boarding a bus...

|

|

For some reason, every photo I took of Mongolian children came out fuzzy, but it is still evident that they are very cute kids. We carried candy and when we stopped at a yert to ask directions, would give a handful to any child present. That usually produced smiles all around. I don't indulge in racial animosities, but learned an ethnic joke from our native Mongolian translator. Given the source, I trust it is not too offensive. The question is, "How do you blindfold a Mongolian?" The answer is, "You use a shoelace".

|

|

|

The trip home was a bit of a nightmare.

|